A Notemaking System For Compounding Knowledge

Investing in a tool that maximizes your greatest asset—reason—is one of the smartest choices you can make.

What if there were a system that enabled you to grow your knowledge the way Warren Buffett grew his wealth? Buffett credits compound interest as one of the primary reasons for his immense wealth.

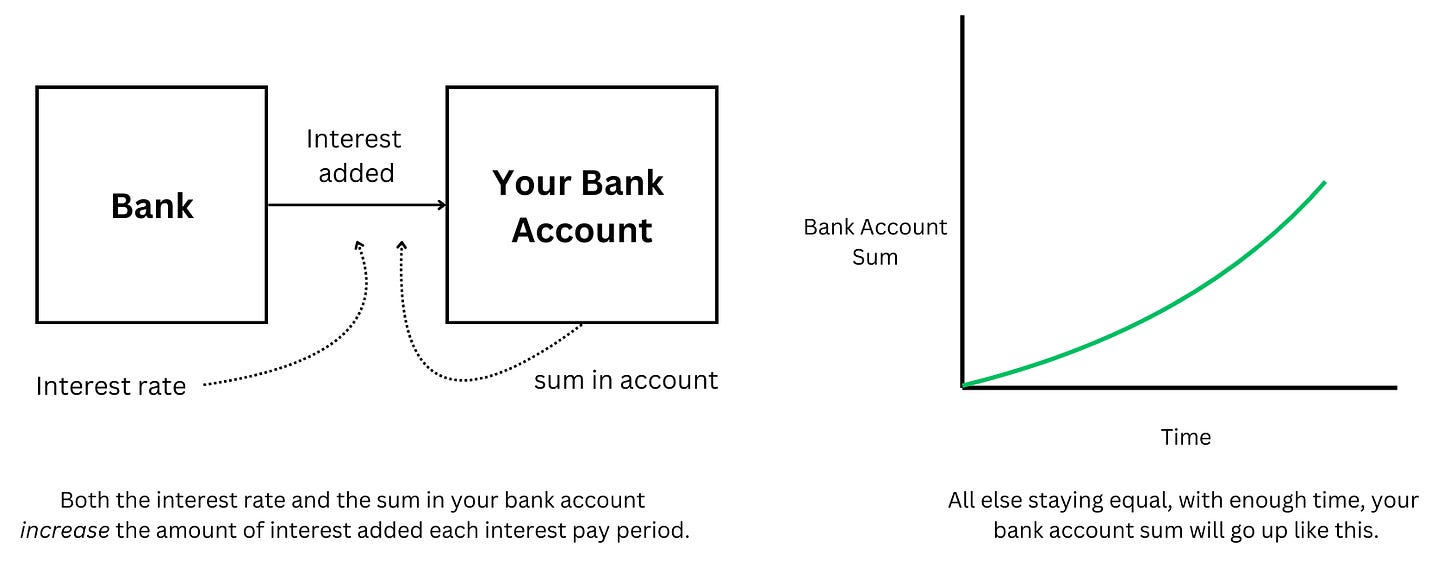

Compound interest is when a bank pays you interest on your first month with them, and then pays you even more the next month due to an increased amount of money in your account, and so on month after month. See the image below.

Compound interest is a feedback loop for becoming wealthy. But, how do we apply this to knowledge? And, first, what does it even mean to “compound” knowledge? And, why should you care?

Compounding knowledge is about creating a feedback loop to grow the value of your ideas—just like interest creates a feedback loop that grows the value of your bank account. This doesn’t mean collecting reams of data from others you’ll never use (as traditional note-taking urges us to do). That’s worthless—nearly as worthless as hoarding Monopoly money. Rather, this means snowballing the best lessons, methods, concepts, and ideas you’ve learned, created, and successfully applied over the years to create a reservoir of potential. Instead of just growing your spending potential, this system grows your creative potential. Just as each of your dollars can become a source for more dollars, each of your ideas can become a source for richer ideas. You just need the right kind of feedback loop.1

Many personal knowledge management systems (PKMS) attempt to achieve this goal. However, the only PKMS I’ve found that does this is the Zettelkasten system and its variants.

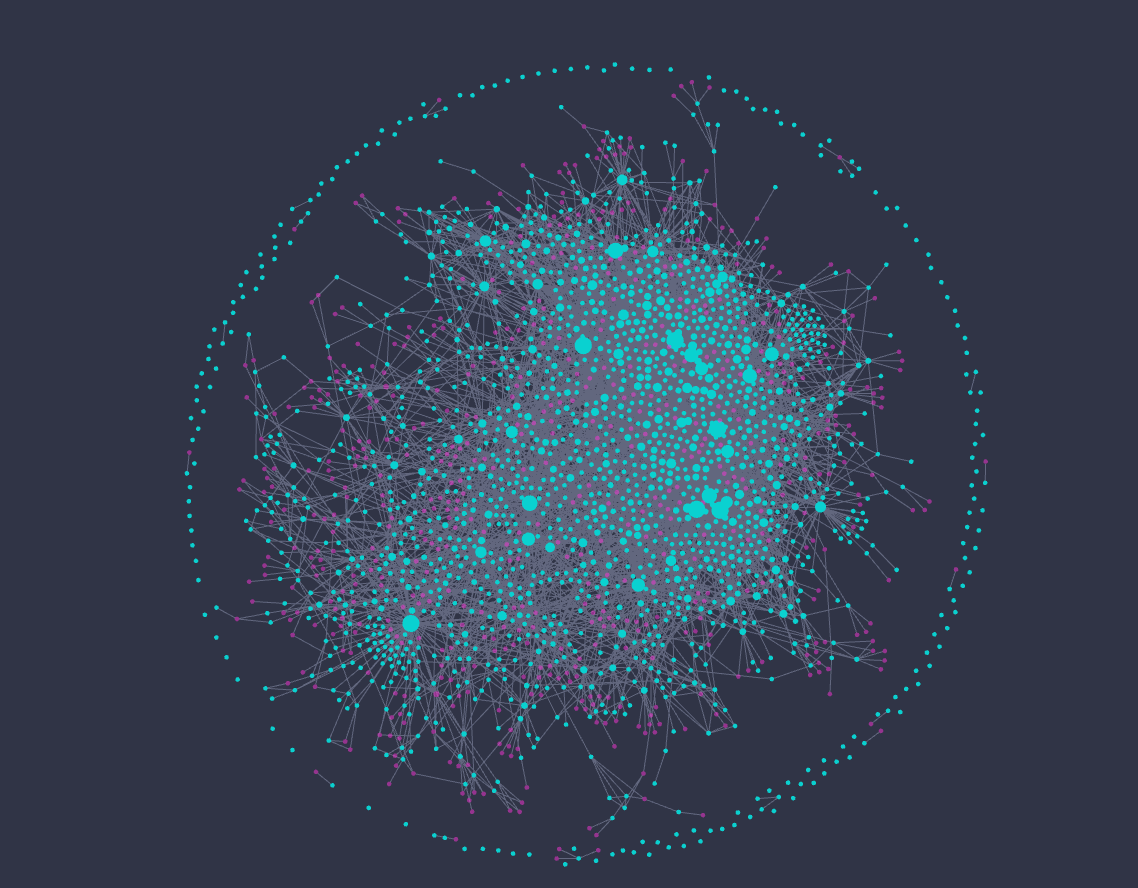

How does the Zettelkasten system do this? It does so by linking your ideas into an ever-improving network with a simple feedback loop—Spark, Remark, and Relate. But, before we explore that, here’s a short history to help you understand the Zettelkasten system better.

A Short History of The Zettelkasten System

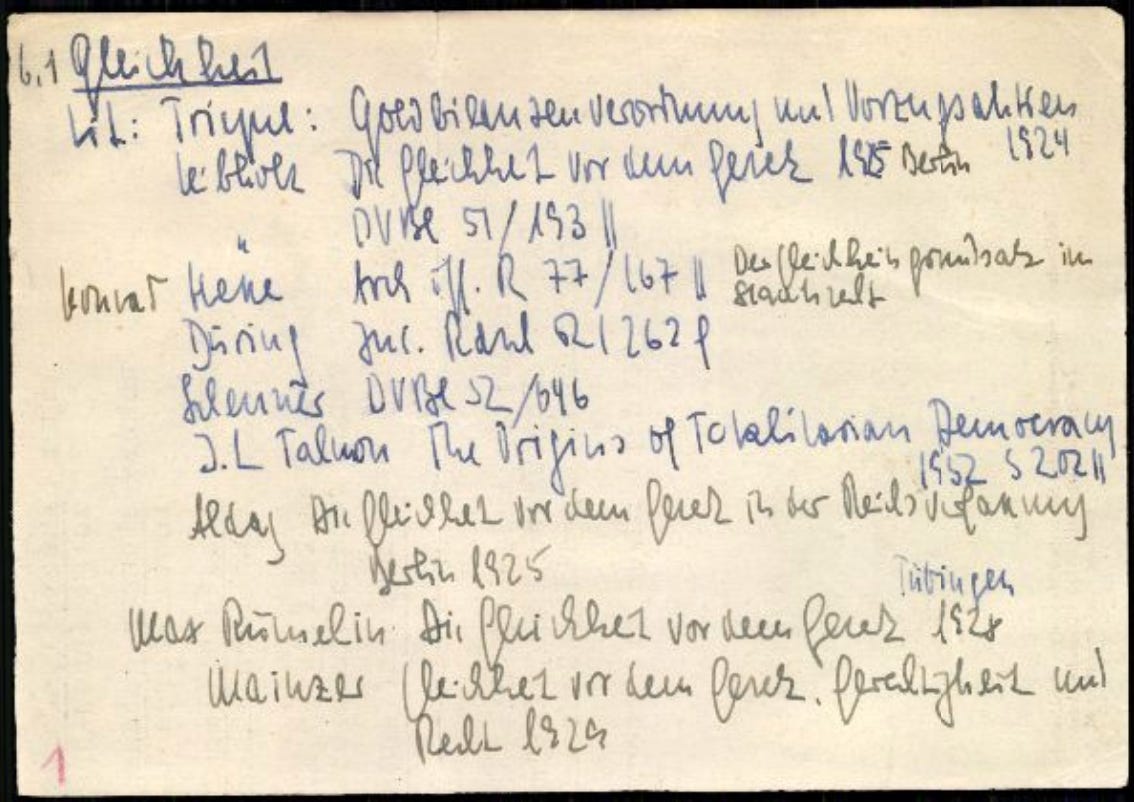

The Zettelkasten system was first developed by the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, who wrote prolifically using it—about seventy books and four hundred articles. “Zettelkasten” translates roughly to “note box.” His system involved a large, wood cabinet that contained nearly one hundred thousand “zettels” or paper slips. Each of these slips had a single idea, an identifying code, and the codes of slips with related ideas on them.2

Today, we have software that makes creating and using a Zettelkasten system much easier. I use a software tool called Obsidian. But as long as the tool has the basic functions the Zettelkasten method requires, it doesn’t matter if your Zettelkasten is physical or digital. You just need to be able to create, edit, and link notes—Obsidian checks all of these boxes.

The Basics of Using a Zettelkasten System

The foundational feedback loop of using a Zettelkasten system is three steps:

Spark

Remark

Relate

I like to call this “The SRR Method” for short.3

The first step of this method is to capture ideas or “sparks.” What this means, in practice, is writing down (in your own words) an idea, thought, or observation that makes you go “hmm” in a brand new note (or in your notes on a source). For example, if I’m capturing ideas from a YouTube video, I may type two double brackets like this “[[“ to create a “placeholder link” for that idea (Obsidian has this functionality). And, if you hover over this link, you can create a new, blank note by the name of that idea if you so please.

Alternatively, if I’m capturing a thought ad hoc, I could create a brand new note like this:

This step creates an “atomic note”—a note expressing a single idea. Also, it’s very important you write atomic notes in your own words. This helps you “own” the idea, making it an integral part of you, rather than turning yourself into a stenographer or information hoarder. (The upcoming third step, relate, becomes more difficult over time if your Zettelkasten is filled with ideas you don’t understand, and therefore, can’t relate to.)

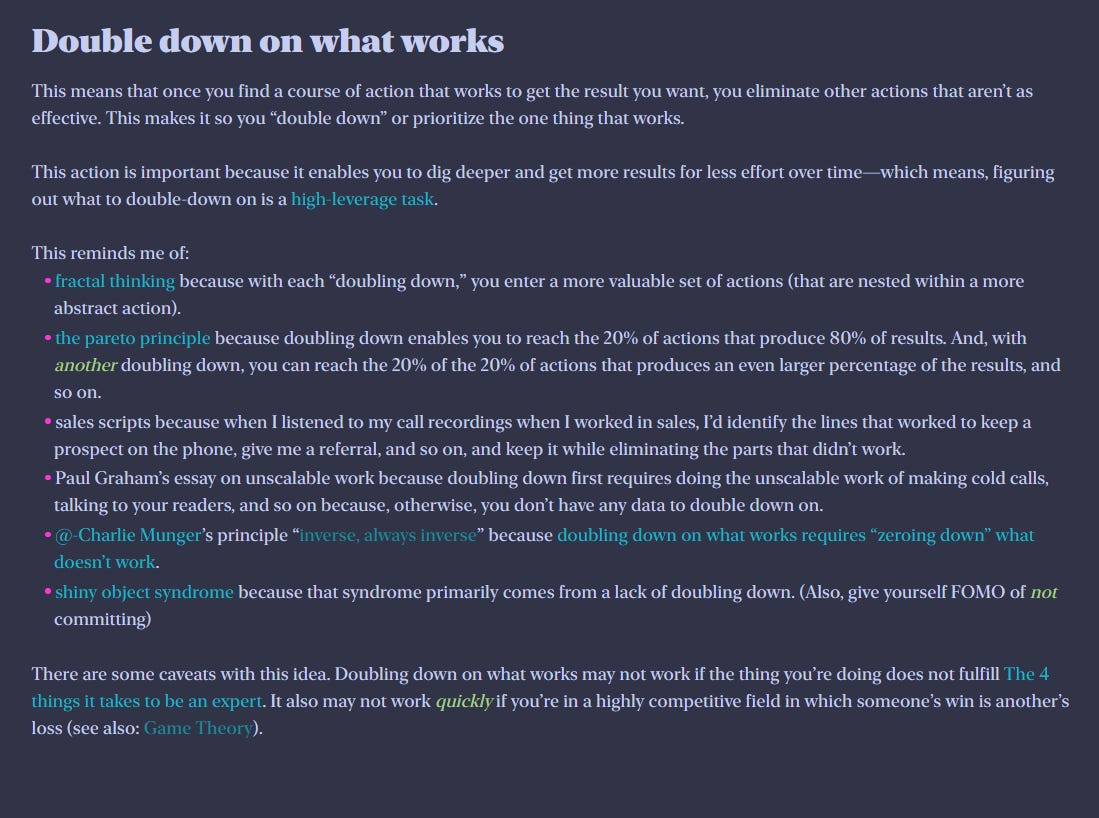

For an example of an atomic note, I have one titled “Double down on what works.” In this note, I briefly explain the meaning of the idea, its importance, and what it reminds me of and why. The blue text links to other notes that follow a basic structure similar to this one. (The many links you see here come from completing the next steps.)

The next step is remarking on your spark. A remark is just something you want to say about the idea you just captured. This could mean explaining the meaning of the idea, if it needs explaining, or completing sentence fragment prompts like “This is interesting because. . .” to generate remarks. From these prompts, you may find yourself recalling and linking to preexisting notes or creating new placeholder notes, which leads us to the next and final step.

Step three is when you relate your new note to another note. In Obsidian, you can do this by typing a double bracket and the name of the note (E.g. [[Double down on what works]]). There are many reasons to relate (or link) atomic notes to each other, but the fundamental reason why is that those connections are meaningful to you. Relating notes based on relationships others have established is fruitless and counterproductive. You’re just doing work that’s already been done—and, worse, you’re much less likely to memory encode the connections for yourself and miss out on the value found in learning ideas deeply and thinking creatively. The primary value of this system is found in making creative connections for yourself. Be self-interested. Don’t stop yourself from making new connections by adhering to a canonized hierarchy of knowledge that may have been conditioned into you in school or elsewhere.

Atomic notes, and their connections, are a key aspect of compounding your knowledge because you can write them using the smallest units of thought— sentences—or, if they capture a single concept, they form the basis of thoughts. They’re like building blocks for later thinking, later compounding.

As you can see, the basic steps involved are simple. However, don’t let its simplicity fool you. There are many benefits of organizing knowledge in such a way.

One benefit is you can resolve contradictions in your ideas over time. As you capture sparks and revisit old thoughts through linking, you can apply old learnings about how your mind works to future events. Or, you can discover flaws in your thinking.

Here’s an example. In my last post, I wrote about how reading your old journal entries can improve your objectivity about your past thoughts by giving you distance from your emotions surrounding those thoughts at the time.4 The cool thing is the third step of The SRR Method—relate—gives you the same benefit because it pushes you to reexamine old notes as you relate new ones to them. Equipped with distance from past emotions and new knowledge, you may see an old atomic note contains a wrong idea. You have two options. You can either update it or keep it as a record of your own folly—a pattern of thinking to be avoided again in the future. Imagine if you had an ever-compounding record of your mistakes you could refer to. How likely would you be to commit those mistakes again?

Another benefit of this system is creating digital assets from the bottom up—i.e. through divergent thinking-made connections (I’ll talk more about this in future posts). For example, as you add more atomic notes, you may reach a “mental squeeze point,” as Nick Milo puts it. This is when you’ve created so many atomic notes that it’s hard to navigate them, so you need to create another that you use to organize them into a structure. These organizational notes are called “Maps of Content” or MOCs for short. The value of MOCs is they become bottom-up-created, living digital assets that become “Wikipedia pages” for navigating and finding ideas you can use to solve problems or do your best work.

Another bonus of this system is you can tend to and merge similar ideas over time and choose more precise statements of those ideas. In fact, while I was writing the last paragraph, I noticed that my atomic note about “bottom-up thinking” was very similar to my note on “divergent thinking.” I looked at both of them side by side, then realized one was more precise than the other, so I merged the two. (You can also keep the less precise one as a record of “what not to think.”)

As you can see, the Zettelkasten system can help you compound:

Knowledge about yourself.

Ideas from your favorite subjects.

Your thinking abilities.

The deepest reason this system is valuable is because it helps you develop and maximize the use of your greatest asset—your reason. All of the amazing, creative things people have built and made—spaceships and skyscrapers, novels and movies, refrigeration and one-day shipping, and this system itself—came from the intentional, active use of this faculty.5 Anything that helps you use the thing that makes those amazing, life-serving values possible is objectively good.

Hopefully, this post gives you a taste of what the Zettelkasten system involves and what its benefits are. This may help you get a start. But, if you enjoyed this post and are excited about how to build a Zettelkasten of your own so that you can compound your knowledge and enhance your understanding of reality so that you can flourish in reality, please like, share, and comment on this post so I know what kind of content to keep making.

For more on feedback loops, I recommend Thinking in Systems by Donna H. Meadows.

Luhmann’s system foreshadowed hyperlinks.

These steps are not mine. They were developed by Nick Milo. They’re the easiest steps I’ve found for maintaining a sustainable notemaking habit, so that’s why I’m using them.

The anecdote in my last post is a case in point of the power of a Zettelkasten. I would have never recalled that anecdote without my Zettelkasten.

For more on reason, its role in life, and its alternative, consider reading

’s Reason vs. Mysticism: Truth and Consequences. This essay changed my life for the better, forever.

I switched from Roam to Obsidian a few weeks ago, I’ve been happy! I definitely enjoy the Zettlekasten method.

This is an awesome overview, thanks for sharing!